I got interested in this story when I looked at an exhibition on in London which had caught my interest. The exhibition was on Artemesia Gentileschi - the most important woman artist of the 17th century. One of her key works is that of Judith beheading Holofernes and when I posted the Klimt thread, I realised he also had painted that scene along with lots of other artists, so I thought it would be interesting to compare them and see the different approaches.

Unless otherwise stated all quoted information is from www.artsy.net

First we need the story which is from the Book of Judith in the Old Testament.

From www.artsy.net:

As the ancient story relates, Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar sent his general Holofernes to besiege the Jewish city of Bethulia. Judith, described as a beautiful young widow, resolves to save her people by slaying Holofernes herself. After reciting a long prayer to God, she dons her finest clothes in order to seduce him. After Holofernes has drank enough wine to become intoxicated, Judith decapitates him with his own sword, winning a decisive victory for the Israelites.

Botticelli, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, ca. 1470. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The reason for so many depictions and interpretations is given on artsy as follows:

In particular, the story provides the ideal template for the exploration of the power of female virtue, beauty, and power. Consequently, there is a rich array of artworks depicting Judith, which mainly fall into two categories: the femme forte (the strong and/or virtuous woman) and the femme fatale (the sexually dangerous woman).

early Renaissance depictions of Judith by Florentine artists nearly always appear virginally beautiful. Sandro Botticelli’s depiction of Judith returning to Bethulia with the head of Holofernes (ca. 1469–70) similarly presents her like a goddess; in the painting, she dons a chaste, yet richly draped, dress.

Donatello, Judith, 1457–64. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

www.artsy.net

To underscore the political allegory, Donatello portrayed Judith in a warrior’s stance, her sword raised, poised to strike at Holofernes’s exposed neck. Her head is modestly covered, like depictions of the Virgin Mary, but her face has Classical features, also aligning her with virginal Greek goddesses such as Artemis or Athena (the ornament on her neckline is reminiscent of Athena Parthenos’s breastplate).

Giorgione, Judith with the Head of Holophernes, 1504. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

www.artsy.net

With the onset of the Renaissance, interpretations of Judith became more politicized. She came to symbolize a small but strong population able to overpower a tyrant.

By the late Renaissance, depictions of Judith had become more seductive and aggressive. Starting in the early 1500s, artists transformed her from a relatively simply dressed goddess figure into an elaborately adorned noblewoman.

One can see the first signs of this shift in Giorgione’s 1504 portrayal, in which a triumphant Judith steps on Holofernes’s severed head. She is fully clothed in a simple dress, but Judith’s bare leg—the very same leg with which she steps on Holofernes’s head—emerges from a long slit in the garment, and jewels adorn her neckline and her head.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, ca. 1530. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

the Judith portrayed by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1530 wears a lavish, court-appropriate outfit that shows her, as the Metropolitan Museum of Arthas written, “dressed to kill.” Although she is clothed in this iteration, her facial expression conveys a self-assured sense of power and seduction that departs from previous Judiths, whose faces are usually unperturbed or simply coy.

Giorgio Vasari, Judith and Holofernes, ca. 1554.

In 1554, Giorgio Vasari dressed his quite-muscular Judith, shown in the act of lowering her sword onto Holofernes’s neck, in a pale pink cuirass paired with a multi-tiered, green skirt clasped with a gilded girdle. These unusual garments suggest both martial strength and feminine seduction.

Caravaggio 1598 - 1599

From Artsy:

During the Baroque era, Judith beheading Holofernes became an opportunity for painters to indulge in gore; in works from this period, Judith appears as more of a violent assassin than a virtuous woman or seductress. In 1599, Caravaggio, for instance, painted an explicit depiction of the very moment Judith cuts Holofernes’s throat, his face looking up in disbelief as his body still struggles. Caravaggio’s Judith, who is young and blonde, looks almost awkward as she decapitates the Assyrian general.

Artemisia Gentileschi 1620 (one of the first women to pursue a career on the same terms as men).

Artemisia'a Judith

has been interpreted by historians to convey the artist’s female rage, both as a rape victim and as a woman in a male-dominated field. In both paintings, Judith, richly dressed, is aided by her maid in pinning Holofernes down as she decapitates him. The paintings convey the physical exertion experienced by the three characters, and, in contrast to Caravaggio’s, shows Judith unafraid of the task at hand.

It wasn’t until the Belle Époque that Judith fully morphed into a desirable—but markedly depraved—femme fatale. While this archetype has always existed in art and literature (popular femmes fatales include Medusa, Cleopatra, Salome, and Delilah), it became a particularly popular subject for artists during the Romantic period and flourished in the late 19th century, when female figures were shown with an equal combination of beauty and turpitude.

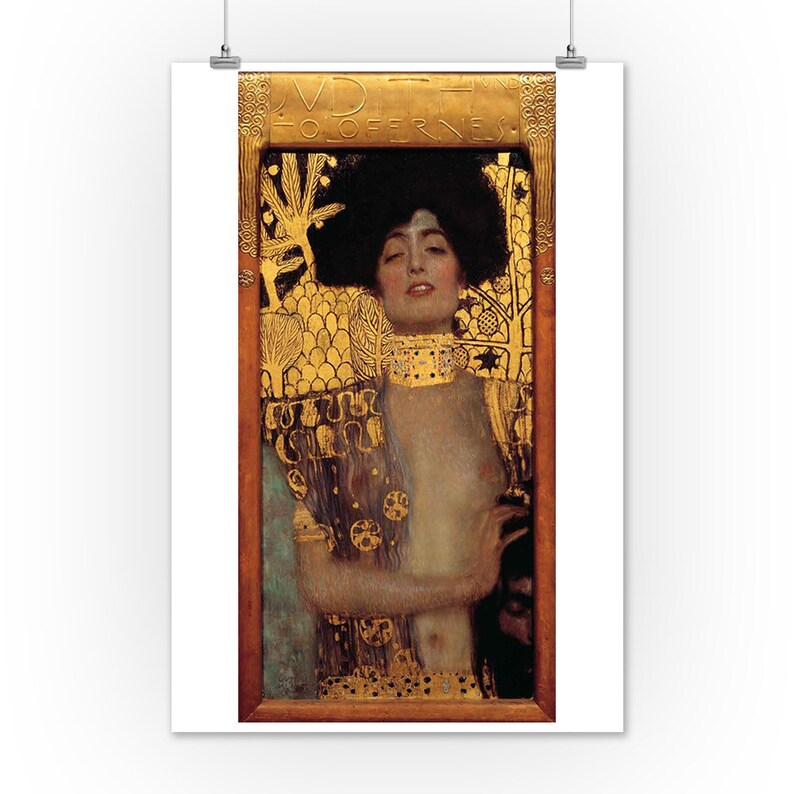

Gustav Klimt 1901 Judith and the head of Holofernes

Gustav Klimt’s 1901 version of Judith (which was mischaracterized as Salome for years, even though the frame distinctly bears the title Judith und Holofernes) ignores the once-prevailing heroic narrative to picture her mostly exposed, cradling Holofernes’s head in an expression of post-coital bliss. Here, Holofernes, whose head is cut out of the frame, is not the victim of a female warrior, but of a sheer seductress.

Franz Stuck, Judith, 1928. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Similar in style is Franz von Stuck’s 1928 version of Judith. A purveyor of mythology and female nudes, the German artist painted her full-frontal, wielding the sword with two hands, an expression of spite and triumph on her face. German author Eva Schumann-Bacia described this take on Judith as “the epitome of depraved seduction.”

In 2012, American artist Kehinde Wiley realized a more contemporary interpretation of the tale, depicting Judith as a black woman in a Givenchy gown. Holofernes’s severed head is here a white woman, a symbol of the need to vanquish white supremacy.